- Home

- John Lurie

The History of Bones

The History of Bones Read online

Copyright © 2021 by John Lurie

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Random House and the House colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lurie, John, author.

Title: The history of bones : a memoir / John Lurie.

Description: New York : Random House, 2021.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021004403 (print) | LCCN 2021004404 (ebook) | ISBN 9780399592973 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780399592997 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Lurie, John | Composers—United States—Biography. | Jazz musicians—United States—Biography. | Saxophonists—United States—Biography. | East Village (New York, N.Y.)—Social conditions—20th century. | LCGFT: Autobiographies.

Classification: LCC ML410.L96365 A3 2021 (print) | LCC ML410.L96365 (ebook) | DDC 780.92 [B]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021004403

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021004404

Ebook ISBN 9780399592997

randomhousebooks.com

Book design by Susan Turner, adapted for ebook

Photo insert design by Stephanie Greenberg

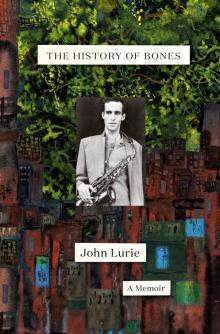

Cover photographs: © Tim Lee

Cover paintings: John Lurie

ep_prh_5.7.0_c0_r0

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter 1: Boy Boy

Chapter 2: The First Time They Arrested Me, I Actually Was Drunk

Chapter 3: Inside God’s Brain

Chapter 4: I Come from Haunts of Coot and Hern, or, I Didn’t Kill Yogi Bhajan

Chapter 5: I Am the Supreme Totality!

Chapter 6: Dancing Hitler

Chapter 7: Crushed Bandit

Chapter 8: Men in Orbit

Chapter 9: The John Lurie School of Bohemian Living

Chapter 10: An Erection and an Alarm Clock

Chapter 11: Paris. Vomiting and Then More Vomiting.

Chapter 12: Udder and Horns

Chapter 13: Mutiny on the Bowery

Chapter 14: Look Out! The Anteater!

Chapter 15: Gaijin Sex Monster

Chapter 16: Hung There Against the Sky and Floated

Chapter 17: Fifty Million Junkies Can’t All Be Wrong

Chapter 18: I Was Instructed to Slouch Down to Eat My Sandwich

Chapter 19: If the Lounge Lizards Play in the Forest and No One Is There to Hear It…

Chapter 20: Hello, I Am a Dilettante and a Hack

Chapter 21: Fifty Million Junkies Are Probably Wrong

Chapter 22: Werner Herzog in Lederhosen

Chapter 23: All the Girls Want to See My Penis

Chapter 24: The Stick, to Whom All Praise Is Due

Chapter 25: Cheese or Hats Are Preferable

Chapter 26: Socks! Socks! Socks!

Chapter 27: What Do You Know About Music? You’re Not a Lawyer

Chapter 28: The Handsomest Man in the World

Chapter 29: When Life Punches You in the Face, You Have to Get Back Up. How Else Can Life Punch You in the Face Again?

Chapter 30: Splobs

Chapter 31: I’ve Run Out of Madeleines

Chapter 32: Flies Swarm All Around Me

Chapter 33: The Last Time I Saw Willie Mays

Chapter 34: My Friends Cover Their Faces

Chapter 35: John Lurie: Pathetic and Ignorant

Chapter 36: Voice of Chunk

Chapter 37: Rasputin the Eel

Chapter 38: It Never Hovered Above the Ground

Chapter 39: Giant Diving Bugs Bombing Our Faces

Chapter 40: Fifteen Minutes Outside of Nairobi, There Are Giraffes

Photo Insert

Acknowledgments

About the Author

1

Boy Boy

Just a speck. At the top of its arc, a mystical thing suspended against blue. Then it would come hurtling down and thwack to the earth. Always out of my reach.

My father could throw a ball, incredibly high, straight up into the air. I loved being hypnotized as it hung up against the sky, this thing that was no longer a ball. It wasn’t really even a game of catch, because I could never catch them at that age.

We used to sit on the couch listening to the stinking Red Sox on the radio. I loved the smell of him, there was warmth in it.

“You’re a foxy little newspaper.”

My dad laughed. He was waking me up to go fishing, and this was something I said that was left over from a dream.

When I was a kid we used to go fishing on Saturday mornings. He’d wake me really early and we’d go out, both so tired we’d be laughing like idiots at everything. Boat stuck in the reeds. Incredibly amusing! You had to be there.

On the drive home, we saw an old lady in a fur coat hunched over the wheel of a convertible sports car. Her white hair flapping wildly in the wind. She pulled alongside us, hovered there for a moment, and then whizzed off, like we were standing still. Tears rolled down my dad’s face.

He wasn’t much of a fisherman and didn’t take it seriously. He just liked to be out in a boat with his son on a nice morning. He called me “Boy Boy.”

“You want to go get something to eat, Boy Boy?”

The throws got lower and lower until it wasn’t so exciting anymore.

* * *

—

I went to high school in Worcester, Massachusetts. A horrible place, Worcester has a dome over it so that God is not allowed in.

The first thing that emerges when I think of Worcester is a metal pole.

I am familiar with its molecules. I know its deepest essence.

The pole was a railing around someone’s front yard on Pleasant Street, near Cotter’s Spa. It was about two and a half feet off the ground. Steve Piccolo and I used to try to balance on it and then walk from one end to the other. We’d get halfway, wobble, and then fall off. We never made it all the way to the end. One night, when I was fifteen, we took mushrooms and crossed it several times with ease. That was how I got to know the metal pole on a molecular level. That was the same night we went into Friendly’s, grinning insanely, and said, “We’d like to exchange these quarters for ice cream.” We held the quarters in the palms of both hands, displaying them like they were gold doubloons.

They threw us out.

The first time I had sex was with a girl named Crystal. I was sixteen and Crystal was, I guess, twenty-five. We were in a hippie crash pad, sitting at this filthy kitchen table strewn with pot seeds and Twinkie wrappers. After the last person had passed out, we found ourselves alone. Crystal was a groupie and very proud of it, so I thought I had a good chance, but had no idea how to go about it. I sat there for a long time, not knowing what to do. Finally, I summoned the courage to take her hand and put it inside my fly. Crystal, not resisting, said with complete indifference, “I guess we can ball.” We went into this crummy room with a mattress, with no sheets, on the floor. She took off her clothes. I got on top of her and came in eleven seconds.

Crystal was rumored to have slept with Jimi Hendrix the week before. She gave me gonorrhea. It was nice to have this connection to Jimi through b

acterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

But at that time, my girlfriend was Jeannie, who lived in the neighboring town of Leicester. A waif of a girl with a beautiful face. My parents had rented a cottage one summer on Thompson Pond and that was how I met her. Though I don’t remember meeting her or how she became my girlfriend.

After the summer was over, to go out and see her, I’d borrow the family car and drive about thirty minutes. This is how I learned to play the harmonica, driving with one hand and messing on the harmonica with the other.

I’d pick her up at her parents’ and we’d drive around. Jeannie would jerk me off while I was driving, but only if I used a certain kind of cologne. I don’t wear cologne anymore. I believe that cologne is a good way to gauge somebody’s intelligence: The amount of cologne being inversely proportionate to the IQ. But this was high school and I had to have my hand jobs, so I’d splash on enough to kill a small animal before going to see her.

Jeannie called my cock “Everett.” She would say that she didn’t like Everett because he was always spitting at her.

* * *

—

By this time my dad was on oxygen. The guy who brought the tanks came and went twice a week. Friendly little guy.

The tanks were set up next to the black chair in the TV room. A thin, blue-green tube ran up to a little thing under his nose. When they said that he was going to be on oxygen, I expected he’d be stuck under a tent or have a big mask. I was thankful that this was a little more dignified.

He hated TV. Thought it was stupid. Evenings, before he got really sick, he would sit out by himself in the living room, reading, but the rest of the family was always in the TV room at night. It would have been strange if he was stuck out there by himself in the living room, so we moved the tanks into the TV room with us.

One night, it was just me and him in the TV room. Aretha Franklin was on the TV, performing live at a college.

It was the first time I had heard Aretha and something shocking happened to me—chills went up through my body. I had never had that happen before, heard a piece of music or witnessed something so brave or so beautiful that it made chills happen.

What is this? This sensation?

I was embarrassed to be moved like that. It was so out of my control.

I didn’t want my dad to notice.

She finished the last song with an explosive crescendo and the audience of white college kids leapt to their feet in a simultaneous roar. The reaction was organic and completely correct.

My dad looked so sad and disappointed when he said, “I can see they are legitimately moved. But I don’t feel it at all.”

Isn’t that wonderful? He doesn’t go, “You kids, your music stinks,” because he doesn’t feel it. He sees there is something happening but he doesn’t have the receptors for it, like evolution has been cruel and left him behind.

He was ugly handsome, like Abraham Lincoln.

I was supposed to watch my dad one night but instead went to a club downtown. When I was fifteen, I was mostly hanging out with the black kids, who lived on the other side of Main Street. Playing basketball, going to dances. The black kids were cool.

This wasn’t a dance for kids. Most of the people there were twenty to twenty-five. I was always the only white person there, except for maybe the odd, horrifying blond woman. This was a fairly wild crowd. There were fights. A very muscular air. There were knives and guns.

The next day, Sunday, there was a big scene because I hadn’t stayed home to watch my dad. My mom was always on the warpath on Sundays and she was holding a family council, going on and on about how I had to be aware of my responsibilities to the family. I thought she was being overly dramatic, per usual—my dad was upstairs asleep, she was playing bridge, what’s the big deal, I just decided to go out. This was my dad, did someone really have to stay home and take care of him?

He sat there in his robe and pajamas, not saying anything, looking at the floor.

My dad was beautiful. He was a beautiful man.

When he was in college, he was the bright star of NYU’s literary scene, bursting with potential. He wrote the entire literary magazine under multiple pseudonyms, the other young intellectuals deferring to his greater talents. But when he got out of college, instead of becoming the next James Joyce, as was expected of him, he went off into the South to organize unions for miners. It must have been incredibly rough. But, at sixteen, I didn’t see the bravery in it, nor the altruism. I didn’t know what altruism was.

He started to write his memoirs, but his sickness caught up with him. I thought he had failed. Not because he didn’t finish the book, but because he’d never really done anything of his own. He’d never written any book, when he was supposed to be this great talent. I can’t say that it was disappointment that I felt. It was all the scorn and disgust that a seventeen-year-old psyche could muster toward one’s parents. And he would, now, never be able to do anything about it.

But about a year later, after he was gone, my scorn and confusion were lifted. I was at my cousin’s wedding and all these old guys were coming up to me, showing me great respect. One of them, a short, tough New York Jew with something sweet under the hard cragginess, like Edward G. Robinson, looked me in the eye and said, “You Dave Lurie’s kid?”

“Yes.”

“He was my hero.”

Thank you, tough craggy old man. You freed me.

* * *

—

My best friend at that time was Bruce Johnson. Bruce was incredibly thin, six feet tall, and about one hundred forty pounds, maybe even less. His skin color was more Native American than African American.

He had a lot of brothers and none of them looked remotely alike. He had a brother, Dickie, who hated me because I flirted with his date at a dance once, and another brother, Craig, who had the perfect physique of a Nuba tribesman. In junior high school, I was being disciplined for something and was told to stand in a specific spot and wait to speak to the principal, John Law. For real, the new disciplinarian they had brought in to tame our school was an angry, angry man named John Law.

John Law’s way of controlling the school was to take whoever was brought to his office and hit them really hard in the ass with a paddle. He didn’t even ask what you had done. He just told you to put your hands on his desk and then began flailing away at your ass with his paddle.

Craig Johnson was in his office, and I heard Craig yelling, “You aren’t going to hit me!” And I looked into the office to see Craig and Principal John Law wrestling, each holding the other by the wrist, trying to get the paddle.

Craig Johnson was only fourteen then. But John Law couldn’t get the better of him and he finally let him go. I didn’t move from my specific spot for one moment. That was how scared I was of John Law.

Bruce was the fastest runner in the group we hung out with, and he could jump. He had won the state high jump championship. But he hated sports. I used to have to beg him to play basketball.

One spring night, we were outside a church dance. Someone had bought a bottle of whiskey. Wayne Boykin was making fun of me and the others were laughing. Because of Wayne’s bizarre way of talking, I couldn’t understand what the hell he was saying.

Later that night we were walking by the high school and someone cut up this path into the woods and started to run. Everyone fell in behind him and we were all running blindly through the woods. Someone would just start it and then it would all be happening. Running. There was none of this white kid shit of, “Hey, you guys, let’s go and run in the woods.”

Bruce was coasting way at the back, not interested. When we came out of the woods and onto the empty football field next to Doherty High School, the thing really broke into full speed. Bruce just gently turned it up a notch, came all the way from the back and beat everybody easily. Some of these guys were big deal track stars and Bruce just

decimated them.

Karen Lubarsky sat in front of me for five years of junior high and high school. Every day of that five years I would borrow a pen from her that would always, somehow, disappear before the end of the school day.

I wanted to be on the football team. I wanted to play end but needed to gain about twenty pounds, because I was rail thin. For breakfast I would drink a Nutrament with five raw eggs. At 10:10 a.m. every morning, during third-period French class, I would get these stabbing pains in my stomach. Karen Lubarsky got to the point where she could time them and would turn around with an amused smile just before they occurred. I got even with her by biting off my fingernails and dropping them, lightly, on top of her black, frizzy hair. But you know what? In the end, fuck the cool kids, Karen Lubarsky was the best.

I was with John Epstein, otherwise known as Running Red Fox. We all had idiot pothead nicknames. We were hitchhiking somewhere and a state trooper stopped to tell us that we couldn’t hitch there. This was 1968, hippies were hitchhiking everywhere, and the troopers were always telling you that you couldn’t hitchhike here. They would take you to a back road in the middle of nowhere and say, “You can hitchhike here all you want.”

John had a plastic bag of some pills—I don’t remember what—hanging out of his breast pocket. The trooper said, “What’s this?” and pulled them gently up out of John’s shirt. Then he unrolled John’s sleeping bag and there was a fat bag of marijuana.

He drove us to the station house and put us in adjoining cells. They took our belts away so we couldn’t hang ourselves. We thought this was hysterically funny and attempted to hang ourselves with our shoelaces.

The History of Bones

The History of Bones